In Search of Lost Sounds

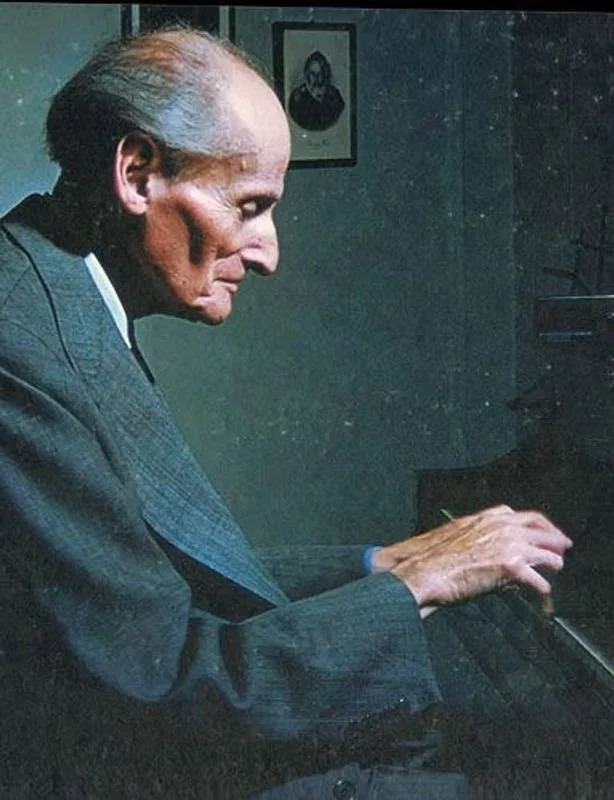

Arbiter Records’ releases give us good reasons to revisit the music of Johannes Brahms with fresh ears. Picture from ca 1866-1867. BRAHMS-INSTITUT/ARKIV

How would our understanding of the classical music tradition differ if recordings from the days of Beethoven and Chopin existed today? Most of us have grown accustomed to hearing recorded performances that are much closer in time to our own era – and thus closer to contemporary ideals and aesthetic preferences – rather than the tradition they reflect. The reason is, of course, familiar: it was only towards the end of the 19th century that it became possible to preserve sound in any meaningful way, and it would still be a long time before the technology was perfected. With today’s demands for flawless playing and impeccable sound quality, older recordings have been discarded and forgotten. But, in so doing, aren’t we discarding a significant link to the past? The few recordings that Brahms made toward the end of his life, to give but one example, are certainly difficult to decipher. But weren’t there people who were close to him, who were perhaps taught by him, and who passed on a tradition that has actually been preserved?

It is around such questions that the Arbiter Records label has explored the history of recorded music and built up a fascinating mosaic of never-before-released artefacts. Bartók pupils have been tracked down in the deserts of California, a forgotten pupil of the legendary pianists Theodor Leschetitzky and Ignacy Friedman has been rediscovered in Egypt, and private conversations and recordings of the pianist Carl Friedberg, who was close to both Johannes Brahms and Clara Schumann, have been unearthed in Australia.

In this age of commercialism, it takes an extraordinary amount of will and enthusiasm to run projects of this kind, and few can be said to have met the criteria as well as Arbiter Records founder Allan Evans has. He heard and befriended the legendary blues guitarist Reverend Gary Davis at an early age and became his last pupil, and while studying composition and ethnomusicology, Evans’ interest in historical recordings turned into an obsession – resulting in a lifetime of detective work that undoubtedly would have impressed even Sherlock Holmes. As an example, it was long believed that the Polish-born pianist Severin Eisenberger had left no recordings behind, but after his death in 1945, his widow received an unexpected delivery. As it turned out, Eisenberger had once told their apartment building’s janitor that he was throwing away his own recordings, but the janitor realised their value and saved them. After Eisenberger’s death, the recordings were passed on to his widow, and – half a century later – a selection became available through Arbiter Records. Stories like this are abound at the label, which rightly dubbed its activities sound archaeology.

***

Undoubtedly, there are good reasons to re-evaluate how we interpret Brahms after listening to the double CD “Brahms: Recaptured by Pupils and Colleagues”. For if there is a lack of sharpness in the sound image, completely new worlds open up as a result: the music takes on a freer, more improvisatory form, and the tempo choices are often significantly more brisk than what we are used to today.

Ilona Eibenschütz heard Brahms play his piano pieces opus 118 and 119 in in private the 1890s, and went on to give the London premiere of the works in 1894, aged 21.

The commonplace idea of sentimentalising the opening of Brahms’ first piano trio is completely turned on its head in Trio New York’s bold interpretation. Similarly, when we hear Ilona Eibenschütz’ passionate and unusually lively performance of the ballade opus 118 no. 3, we should note that Eibenschütz had heard these late opuses as new works – played to her in private by the composer himself. Not long thereafter, Eibenschütz premiered both opuses 118 and 119 in London.

It is a staggering thought to consider that this 1903 recording represents what was modern music at the time. This makes it all the more difficult to return to various modern recordings, which often seem square by comparison. What happened to the elasticity of tempo and all the subtleties that characterised the playing of both Brahms himself and the circle around him?

Hungarian Etelka Freund was a pupil of Busoni and played regularly for Brahms.

Perhaps it is Etelka Freund‘s playing that is the most rewarding among these historical documents. The variations on a theme by Robert Schumann are played passionately and with an elegiac tone, whereas in the selection of Bartók’s “For children”, Freund shows how an entire universe of emotions can be contained even in the shortest and most sparsely notated bagatelles. The fact that she was a friend of both Brahms and Bartók makes it particularly appropriate to include music by the latter here, not least because of Bartók’s great fondness for Brahms’ music. At the same time, Brahms’s interest in the style hongrois manifests itself in Freund’s recording of the rhapsody Opus 119 No. 4, where the playful rhythmic irregularities are performed with great schwung.

As head teacher at what would become the Juilliard School of Music in New York, the German-born Jewish pianist Carl Friedberg (1872-1955) became an influential pedagogue. In 1893, he performed an entire recital of Brahms’ music in the composer’s presence.

Of great value are the oral histories, in which Carl Friedberg and Edith Heymann remember Brahms and Clara Schumann with warmth. The listener is not only brought closer to Brahms’ universe, but Brahms is also gently removed from the pedestal on which posterity has placed him, by people in his immediate circle who not only shine a different light on Brahms the person but also demonstrate with what freedom and flexibility his music can be interpreted. Is it an exaggeration to say that, as the informative CD booklet claims, Brahms’ performance style has more in common with Harlem than Habsburg? Even if as noisy bar would not be the best environment for much of his music, there is an improvisational shimmer to the interpretations Brahms’ closest friends left behind. Who would have guessed that the legendary jazz singer Nina Simone received piano lessons from one of Brahms’ students – Carl Friedberg? The musical content may differ, but what Simone and Brahms had in common was their early exposure to music in bars, in 1950s New Jersey and 1840s Hamburg respectively. Arbiter Records’ disc release gives us good reason to revise our understanding of Brahms and listen to the music with new ears.

The same can be said of “Masters of Chopin”, an impressive four-CD collection that features Ignacy Friedman along with the student he considered the greatest talent he ever worked with – the forgotten Cairo-based pianist Ignacy Tiegerman. Tiegerman’s student Henri Barda is also featured, as is the aforementioned Severin Eisenberger, including his arresting interpretation of Chopin’s Second Piano Concerto. The rediscovery of Ignacy Tiegerman is a story of its own , and the exceptionally pure and poetic piano playing is evident – even where the sound quality leaves something to be desired. The first two movements of Brahms’ Second Piano Concerto are played at a pace unrivalled by any commercial release of the work. The sense of intimacy could hardly be more palpable than in the recordings that seem to have been made spontaneously at home on an upright piano – here I have no hesitation in saying that Chopin’s great F minor ballade has hardly ever been played as heartbreakingly and sincerely as by Tiegerman’s thoughtful fingers.

The untimely death of Allan Evans in June 2021 caused deep consternation in many parts of the music world. His curiosity regarding sound archaeology was infectious. While many of us have been able to enjoy the fruits of this work, few have managed to conduct field studies the way Allan did. All the more reason to take a closer look at the Arbiter Records website and explore all the recordings and in-depth texts available. Why not start with Carl Friedberg’s pedagogical comments on Brahms’ piano music based on his experiences with the composer?

©Martin Malmgren

First published in Hufvudstadsbladet on June 22nd 2020